I'll be honest--the very first time I saw Troy, I liked it. I know, I know! But before you desperately cast about in disgust for a different blog to read, allow me to explain.

It was the year 2004, and my soul mate of a sister had just abandoned me for that new frontier, College. I was lonely, bitter, resentful, and I felt left behind. Out of self-preservation, I was ready to sharpen my knife against whatever leather strop the world could provide. The perfect opportunity came one not-so-very-special weekend. My sister and a few of her snarky friends were coming home, and they all wanted to make fun of see Troy. I tagged along and proceeded to sit through a two-and-a-half-hour bombardment of arrow-pierced thighs, foppish hair, and archaic insults (my personal favorite: "You sack of wine!"). After the movie, they howled in rage and mockery at the travesty of a film, bemoaning its inaccuracy and cherishing the melodramatic dialogue. I joined in like the self-ignorant follower I was, building up my cynical demeanor with snorts and bile. But secretly, I was in love. The reason? I was beginning to discover my love for classics, and this movie was a window into that world. Troy was, albeit, a muddy mullioned window, but it was still a window. For that reason, I, now steeped in the world of classics, cannot be too harsh on that monstrosity of a movie.

Now for the nuts and bolts: I am as big a fan of artistic license as the next person, but the line has to be drawn somewhere. Troy drew the line somewhere back on the beach, where the waves and the incoming ships could mess it up. The first thing I took issue with--no gods or goddesses. What the heck?! If you're going to parade yourself as an adaptation of the Iliad, you gotta include the forces that make everyone's life hell. If it were merely a movie of possible events that could have transpired at the battle of Troy, key players like Achilles and Paris and Helen would have been blissfully absent. But the movie drew on the widely accepted mythology surrounding the battle, and with that necessarily comes the Greek pantheon. The gods are alluded to throughout the movie (Briseis is a priestess of Apollo), but no real indication is given of the importance of the gods in the lives of the ancients. The Iliad demonstrates how the Greeks believed the gods worked in their lives, which is more important for the understanding of Bronze Age Greece than a supposedly "humanitarian" focus. The whim of the gods was how the Greeks explained the crappiness of everyday life--for an event as epically crappy as the battle of Troy, the gods are crucial.

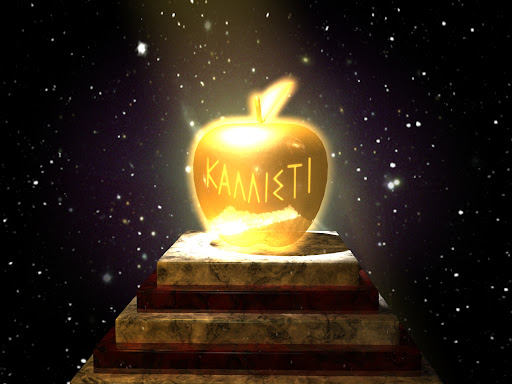

My second issue: the portrayal of women. Now, Bronze Age Greece was certainly not known for its empowerment of women, but in the spirit of severely editing and revising mythology (Hector kills Menelaus? Agamemnon kills Priam?? BRISEIS KILLS AGAMEMNON????), I was hoping that ancient Greek misogyny would hear its swan song--no such luck. The portrayals of Helen and Briseis reflect the worst of ancient Greece and modern Hollywood combined, begging the question of whether the male manipulation of the female image has changed at all since 800 B.C.E. In the Iliad, Helen is portrayed somewhat ambiguously. On the one hand, she is a slave to her love for Paris, her abductor, due to the machinations of Aphrodite (for a recap of the events leading up to the Trojan war, click here.) She is resentful of his weak character, but goes to his bed night after night out of lust (which is inspired by Aphrodite, but is really just a mythological explanation for good old-fashioned, everyday lust. More on that later.) She feels guilty about all the men who have died for her, and even calls herself a "bitch" during an impassioned speech to Hector lamenting her fate. True, such self-deprecations are a constructed female self-image through a male lens, but her self-appointed epithet would have ingratiated her to a Greek audience. Her fate is controlled by the gods, but her reaction to her fate is entirely her own--and it is understandable.

In the movie, Helen is just annoying. She is a willing escapee to Troy who waffles on the issue of whether being with Paris is worth the consequence-laden wrath of her husband. What always brings her back to Paris is her lust for him. Since the gods were nixed out of the film and no effort was made to explain the role of the gods in this epic, Helen's oppressive lust looks like raging hormones--and it is, except that the Greeks would have understood this as the work of higher powers and Helen would have been exempt from the responsibility we place on people with such emotions today. Thus the ancient image of Helen as a generally despised pawn in a game much larger than herself translates to the modern image of a woman who is slave to her emotions and consequently responsible for her own misery and the misery of every soldier at Troy.

Another woman who suffers from the modern twist is the character of Briseis. Her storyline nearly gave me heart palpitations. Not only is her character puffed up to give Brad Pitt something to angst about, but she is also contrived as having a softening influence on the fiercest warrior of all time. Briseis was given to Achilles as a spoil of war, and her reclamation by Agamemnon was an attack on Achilles' pride. He refused to fight in the Trojan war because it would severely impair Agamemnon's chances of winning; Briseis is merely a pawn in their power struggle. Hollywood's love story concoction offends the character of Achilles and objectifies women more than even the Iliad.

The major theme of the Iliad is the wrath of Achilles. He is the greatest warrior of all time; it is his blunt, unforgiving nature which comprises his character. Though the movie certainly tries to emphasize Achilles' fierceness with his mountain-lion-attack style and general disregard for the concerns of others, it makes the fatal error of trying to tame him. Of course, this can only be done with the love of a good woman, but what the movie misses is the more important emotional connection Achilles has developed with Patroclus. They fight each other with swords and words, but underlying this is Achilles' very real sense of protection for his friend (or cousin, or lover, depending on who you talk to). A brawling friendship with another man is probably the only relationship that makes sense to Achilles. It is, therefore, the death of Patroclus that propels Achilles back into the war. The persuasive efforts of all those he might care for have thus far failed, which is what makes the death of Patroclus so significant. Achilles feels responsible for his safety and in his death feels the loss of a true friend. Guilt turns to wrath, and Achilles re-enters the war to avenge Patroclus. His "love" for Briseis in the movie weakens the emotional sturdiness of his character and lessens the significance of Patroclus' death. Indeed, the death of his friend seems like yet another emotional blow in the soap opera of Achilles' life.

Briseis' feelings for Achilles are never explored in detail in the Iliad, but that is hardly necessary. One can assume, however, that she would not have been too pleased to be the sex slave of an invading warrior. In the film, however, her virginal priesthood and stiff upper lip are no match for the raw callousness that is Achilles. In a breathtaking turning point, Achilles' life balances on the edge of a knife as Briseis straddles his figure with a blade to his throat (clever metaphor, huh?). It is for the lives he will take that she must kill him now, she claims, for those innocent lives that she lays on the grenade (and on him) to do the dirty deed. And do it she does. Just when a woman could have asserted herself in this misogynist setting, Achilles disarms her with a kiss and proceeds to deflower her. And she likes it. Briseis changes from a victim of war to a willing conquest. It is worse than Briseis' total lack of voice in the Iliad because the film allows for her self-assertion and then throws it away. Moreover, the audience most likely knows that if Achilles is going to die, it will not be by the hand of his slave. His glory in battle has been referred to throughout the entire movie by every character and his mother (literally); surely, he will die in a manner befitting a warrior. Briseis' attempt to kill him is therefore framed as a pathetic sidestep on his longer heroic journey, turning the character of Briseis into a model of ultimate and inevitable surrender to the male hero.

Wow. I didn't mean for this review to become its own baby. I just get long-winded and passionate about feminism, does it show? At the risk of adding even more to this review, I have to insert that I loved Hector. I thought Troy did a great job of humanizing Hector's character even more than the epic does, and providing a positive example of a good marriage to balance the lustiness of Paris and Helen as well as the whatever-that-is-supposed-to-be-ness of Briseis and Achilles. Also, yay for Peter O'Toole and positive examples of parenting.

It is 4:18 in the morning, and my vocabulary can no longer extend much farther than "yay for...." So with those final sentiments, I bid you adieu as I drift into the land of sleep and rainbows.